A sustained campaign of attacks blazed across the Welsh counties of Carmarthenshire, Cardiganshire, and Pembrokeshire from 1839. Tenant-farmers and labourers, infuriated by increased charges on road travel that made their working lives and finances even more burdensome, took matters into their own hands by destroying tollhouses, gates, and bars in what became known as the Rebecca riots.

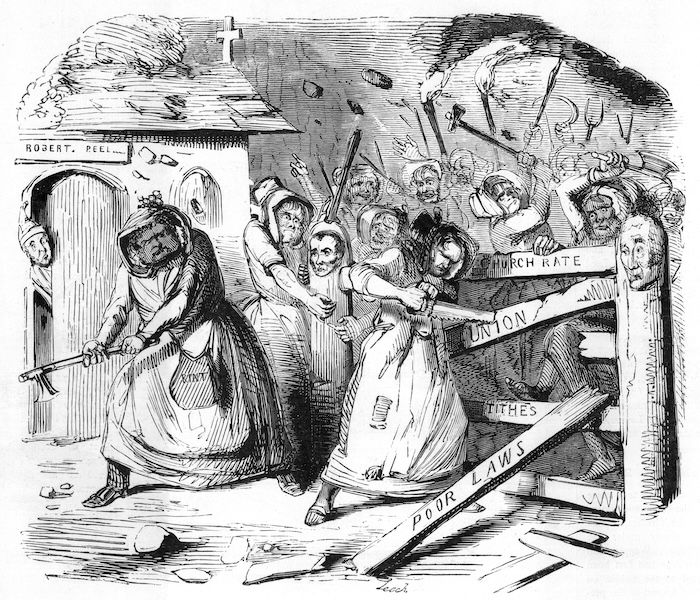

Perhaps the movement’s most recognisable aspect was its enigmatic leader ‘Rebecca’, purported to be taken from Genesis, in which Rebecca is told: ‘Be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them.’ She was represented during protests by a participant in costume that combined masculine and feminine signifiers: a gown or petticoat thrown on over work clothes, or an elaborate wig paired with a false beard.

As the unrest spread across South Wales, reaching its peak in summer 1843, it grew to encompass workhouses, formerly common land enclosed by private landowners, and the estates of the local gentry. Just as the targets of Rebeccaism went beyond tollgates, so their tactics went beyond rioting. Protesters organised mass demonstrations, stormed workhouses, resisted evictions of tenants and auctions of seized property, wrote threatening letters in Rebecca’s name, and collected money for unwed mothers and children. At public meetings, they drew up resolutions to Parliament that echoed the Chartist demand for the secret ballot and the vote for working men.

From the initial resistance to tollgates, Rebeccaism grew into a wide-ranging popular movement coalesced around opposition to the status quo. Although leaderless, somewhat chaotic, and with demands that were broad and sometimes contradictory, at its height it overturned local law and order, commanded almost total solidarity among its supporters, and was referred to in fearful press reports as ‘a formidable insurrection’.

Authorities at the time, from local magistrates to the young Queen Victoria, took the riots more seriously than many subsequent historians have. In June 1843, as the Welsh landed gentry issued urgent calls for military assistance or decamped entirely from their country estates, Victoria’s adviser Lord Melbourne worried that the conflict might spiral into a revolutionary ‘general rising against property’. Robert Peel’s Tory government, already shaken by the rise of Chartism, Ireland’s independence campaign, the general strike of 1842, and, elsewhere in Wales, popular uprisings at Merthyr Tydfil and Newport, sent in thousands of police and soldiers to occupy the area. As resistance continued, the government was forced to take the more conciliatory step of asking the people to air their grievances directly in the 1843 Commission of Inquiry, which spent seven weeks touring South Wales and taking statements from supporters and opponents of Rebeccaism.

As those who testified in their hundreds made clear, the underlying cause of the unrest was a host of longstanding and unaddressed difficulties for the area’s tenant-farmers, labourers, and poor. These included the New Poor Law, workhouses, a cost-of-living crisis caused by falling incomes and high rents and tithes, and an almost-feudal system of local civic and judicial power in which they found it impossible to get their voices heard. In this context, the imposition of charges for use of the roads came as a final straw, and tollgates became a lightning rod for the groundswell of existing discontent.

Far from being – as some radicals sneered at the time – ‘an affair of middle-class farmers’, the Rebecca movement drew poorer farmhands, domestic servants, artisans, industrial workers, and even the commercial middle classes into its ranks. Its cross-class makeup, initially a strength, led to fractures and divisions as labourers and farm servants, recognising the subtle differences in position and interests between them and the farmers who employed them, began to organise separately and articulate their own demands for higher wages and better conditions. Rebeccaism’s demographics also played a part in its rocky relationship with Chartism, which was entrenched in the Welsh coal and iron towns further east. While some leading Chartists cautioned against the class alliances that shaped Rebeccaism, citing the failure of this strategy in the earlier Reform campaign, others welcomed Rebecca as a potential partner in a radical popular front.

Despite the place these events hold in local history and heritage in Wales, they are often remembered only as an isolated outbreak of unrest, a single-issue campaign of direct action against tollgates which, its goals met by Peel’s government with the 1844 Turnpikes (South Wales) Act, subsided as suddenly as it had sprung up. David J.V. Jones’ Rebecca’s Children (1989) was the first exploration of events that acknowledged them as ‘larger than we thought and less respectable’. Meanwhile, in broader histories dealing with the early Victorian age and its transition to industrial capitalism, Rebeccaism tends to remain a footnote or curio, dismissed as a confused or reactionary ‘peasant rebellion’ with little connection to the era’s wider struggles over working-class organisation, welfare, and political reform.

Rebeccaism deserves a more significant place in British radical history – partly because of, not despite, its messier and more militant dimensions. The study of movements like Rebeccaism, with all their oddities and contradictions, can be useful in the context of post-industrial politics and protest. Many recent struggles – from Occupy to the gilets jaunes – seem to be turning towards autonomous, localised, and self-sustaining coalitions in which the traditional conduits of parliamentary democracy are, at best, incidental. Could attention to pre-modern forms of protest offer a guide to the present and future as well as a deeper understanding of the past?

Rhian E. Jones is the author of Rebecca’s Country: A Welsh Story of Riot and Resistance (University of Wales Press, 2024).

#Rebecca #Riots #Wales #Rise