BBC

BBCEileen West has a strange object in her home in Aberdeenshire – a scale model of a huge electricity pylon, built as part of a local campaign against the “monstrous” metal structures.

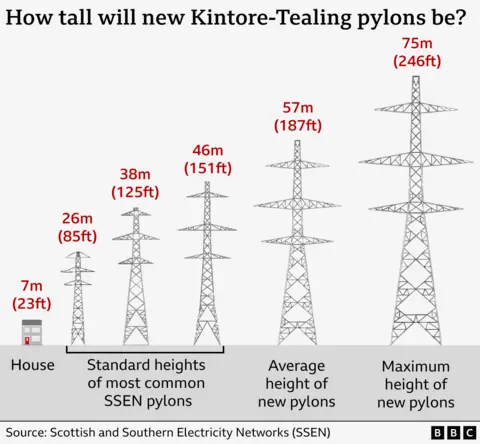

A new pylon line is proposed just a few hundred metres from her home. The steel towers will typically be 187ft (57m) high – significantly taller than most pylons in Scotland. Some could be as high as 246ft (75m).

They are part of a planned 66-mile (106km) route – between the town of Kintore and the village of Tealing – to transfer power from wind farms off the north-east coast of Scotland to where the electricity is needed.

“I think we’re being sacrificed,” says Eileen, a member of Deeside Against Pylons.

The plans are part of one of the government’s key missions, a drive to decarbonise the UK’s electricity system by 2030. Just over half of our power currently comes from wind, solar, nuclear and biomass – organic matter. The government wants to raise that to 95% by 2030 – just five years’ time.

The target is ambitious, and controversial. Energy Secretary, Ed Miliband, told the BBC it is essential to “cut bills, tackle the climate crisis and give us energy security”.

But are local concerns being overlooked to meet national objectives?

BBC Panorama has travelled across the UK – to Aberdeenshire, Lincolnshire and Suffolk – to hear from people in landscapes bracing for change, including Oscar-nominated actor Ralph Fiennes.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has vowed to take on the “naysayers” and “Nimbys” [Not in My Back Yard], who he says stand in the way of national growth by making repeated legal challenges to planning decisions.

That message was underscored last week. Chancellor Rachel Reeves vowed to go “further and faster” in her effort to deliver the government’s growth agenda as she announced a series of potentially controversial new infrastructure projects, including backing plans for a third runway at Heathrow.

A huge construction effort would also be needed to meet the 2030 clean energy target, Mr Miliband told Panorama.

“You need the solar farms, you need the rooftop solar. You need onshore wind, you need offshore wind, you need nuclear. You need all of these things,” he says.

It will also mean more pylons, cables and substations. But what about the local communities who told us they felt they were not being heard and feared their concerns would be overridden?

“The answer is to listen to local people but to make decisions. That’s what our country needs,” Mr Milliband says.

He says the government has committed to provide direct benefits to affected communities via community funds, he adds. People who live near transmission lines could also have discounts on their energy bills.

But Mr Miliband also says: “I can’t say to you local people will have a veto over individual projects in their area.”

For those living in the shadow of these new clean energy projects, the government’s promise to “streamline” the planning process sounds like an excuse for finding new ways to ignore them.

In Aberdeenshire, Eileen West denies she is a Nimby, she says the pylons should not be built anywhere.

“These things will be standing for another 100 years. That’s not a legacy we want to leave our future generations.”

While not against green-energy ambitions, she argues that the government should be exploring alternatives that are less disruptive to the landscape.

“This is outdated, archaic technology. In Europe they do better, investing in proper, modern undergrounding and offshore,” Eileen says.

The Climate Change Committee, an independent body that advises the government on the most efficient way to achieve its climate targets, says the industry has reasons for choosing pylons.

“One of which is cost, in many cases, it’s the cheapest route to delivering clean electricity to people from where it’s produced,” says chief executive Emma Pinchbeck. “And that’s important because ultimately consumers are paying for that infrastructure on their energy bills.

“The second is technical. We’re talking about high voltage lines in many cases. These are really big cables and it’s often better for the physics of the energy system to have them up in the air and accessible.”

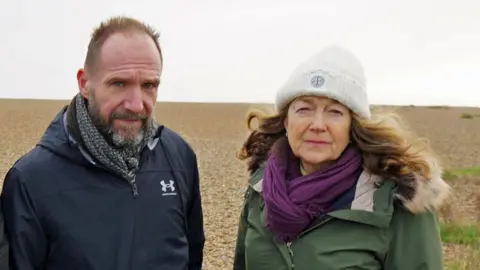

On a windswept beach in Suffolk, we meet Oscar-nominated actor Ralph Fiennes, who is part of a group opposing infrastructure plans in the county where he was born and now lives.

“Governments can, with easy disdain, use the word ‘Nimby’,” he says. “It’s easy, but they don’t live here.”

The county is a potential hub for new energy projects. Miles of trenches may be dug for cabling, large new electricity substations and converter stations have been proposed, and plans for offshore wind farms have already been approved.

Like Eileen in Aberdeenshire, Fiennes questions the impact on the local landscape and whether alternatives like building offshore grid infrastructure and using undersea cabling so the electricity can be brought ashore on former industrial sites are being overlooked.

“We need this energy. The planet is lost without it,” he says. “But what’s the best version of bringing in this green, clean energy?”

William Rose meets us on the farm in Lincolnshire he has run for more than half a century. Nearby, three large solar farms have been approved and another is proposed. Soon the fields could be full of ordered ranks of metal frames holding millions of shiny solar panels.

Like many other protestors, William isn’t opposed to renewable power in principle – he has rooftop solar panels on one of his barns and a small number in a field which power his grain-drying barn.

But he says local farmers are being offered a lot more for hosting solar panels than they could earn growing crops in their fields.

“Generally on corn arable land, you’d expect a return of maybe £200 an acre,” William explains. “And they’re being offered £1,000 an acre a year, index linked for 50 years.”

But he says this comes at a different cost. “What they’re doing is consigning the countryside to this industrial wasteland of solar panels.”

Ed Miliband says the changes would benefit businesses and families across the UK who have been affected by the cost of living crisis – which he says was caused by dependency on fossil fuel markets “controlled by dictators and petrostates”.

But is that worth the impact on local communities and landscapes?

“I’ll have a profound sense of sadness that there would be the desecration of this part of England when there is a better alternative,” Ralph Fiennes says.

Ed Miliband now has the tricky task of striking a balance between those kind of local concerns and his big national target.

#Pylons #people #battle #lines #drawn #UKs #green #energy #plans