:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/ff/03ff088c-e3b2-4442-bb10-d48969be918b/tj-weather2.jpg)

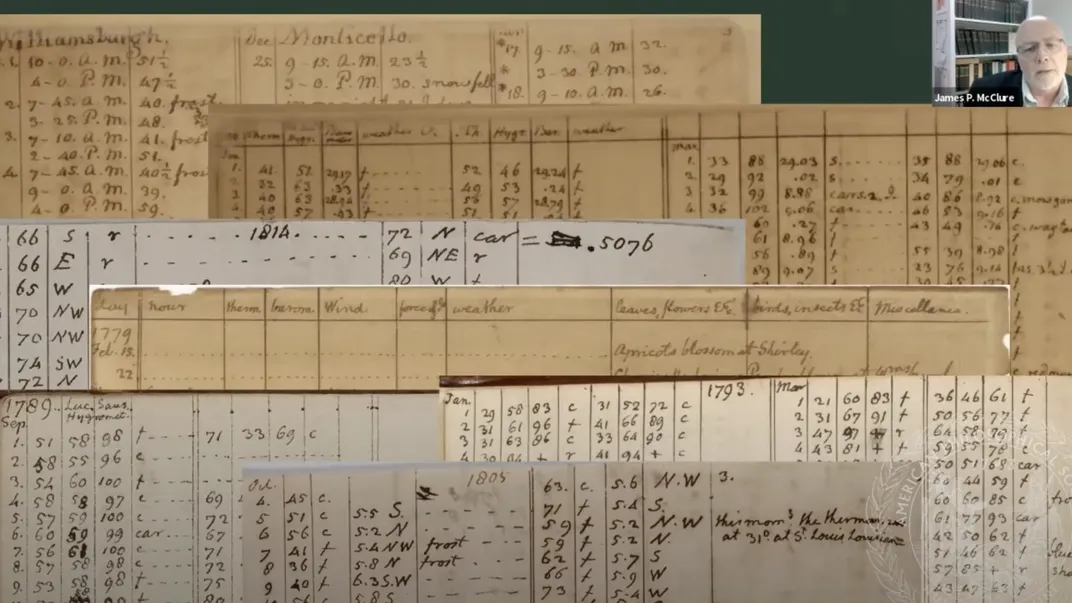

Between July 1776 and June 1826, Jefferson recorded weather conditions in 19,000 observations across nearly 100 locations.

Illustration by Meilan Solly / Images via Wikimedia Commons under public domain and the Jefferson Weather and Climate Records

The Declaration of Independence was off to the press, so Thomas Jefferson spent July 4, 1776, in search of a decent thermometer. By lunchtime, a breeze ruffled the red brick of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. Rain clouds tumbled in. A southwest wind swung through the streets, setting tavern signs to wheel and squeak, but the skies held. The city’s brutal summer melted into mild. Jefferson, a citizen scientist who tracked the weather wherever he went, grew eager to get a reliable read.

On Second Street, Jefferson nipped into John Sparhawk’s busy London Book-Store. Crowned with a unicorn and mortar logo, the emporium boasted new medicines, literature and “an assortment of curious hardware.” Out sprawled a wild sea of glass eyes, silver spurs and mystery elixirs locked into filmy jars. Jefferson waded in. He scooped up a brass, glass and mercury thermometer for the modern equivalent of more than $500. He also bought gloves and made a charitable donation that day. Yet his prized thermometer—a scarce luxury in young America—stands out.

This page from Thomas Jefferson’s memorandum book describes how the third president “pd Sparhawk for a thermometer” on July 4, 1776./https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d3/d7/d3d7ecfc-5379-40f7-a0a6-5a01df106746/3864memop11_lg.jpg)

Jefferson was a gadget guy at heart. Gifted at math and natural science, the United States’ third president “gave time and energy to particular problems that interested him,” says James P. McClure, general editor of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson project at Princeton University. His exquisite geekery knew no bounds. “Nature intended me for the tranquil pursuits of science, by rendering them my supreme delight,” Jefferson reflected in 1809, as he prepared for post-presidential life. “But the enormities of the times in which I have lived have forced me to take a part in resisting them, and to commit myself on the boisterous ocean of political passions.”

Jefferson’s tinkering began with his father’s toolkit. Peter Jefferson left him an expert surveyor’s know-how. His son bought up the tools of the trade and put them to use, running chain lines late into his life. Jefferson kept a 66-foot “Gunter’s chain” to measure acres, a surveying compass or “circumferentor,” and a telescope-equipped theodolite that covered every angle as he tallied elevations. He stuffed his private papers with delicate designs for lamps, canal plans, pasta machines and plows.

No matter the politics of the day, Jefferson tethered his gaze to earth, soil and sky. Revolutions roiled America and Europe for a half-century, but Jefferson held fast to noting weather’s daily whirl. He was curious to see where it carried the animals, plants and people that only “nature and nature’s God” might govern. His was a small and steady habit, vital for a politician who saw America’s future spelled out in farmers’ success. “Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens,” Jefferson wrote. “They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country and wedded to its liberty and interests by the most lasting bands.”

A bronze theodolite, 1800/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1b/58/1b588fd5-a341-4f59-8b04-23a38543b475/munich_-_deutsches_museum_-_07-0008.jpg)

Between July 1776 and June 1826, Jefferson recorded conditions in 19,000 observations across nearly 100 locations. All of this data is now available in a special digital edition of his climate and weather records, thanks to the Papers of Thomas Jefferson project and the Center for Digital Editing at the University of Virginia. The president left a meticulous interpretation of how the world, from Monticello to Paris, met with meteorology. Hunching over details, Jefferson took daily readings at sunrise and in the late afternoon. He tried to get a good fix on low and high temperatures. He logged barometric pressure, air moisture (hygrometer readings), wind direction and force, precipitation, and the ebb and flow of natural phenomena. He saved this data in ledger books, memorandum books, almanac sheets or loose folios.

Weather gossip filled his incoming mail with friends, like James Madison and Ezra Stiles, who sent diligent reports. “Adieu my dear papa,” daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph wrote in a July 2, 1792, missive. “The heat is incredible here. The thermometer has been at 96 in Richmond, and even at this place, we have not been able to sleep comfortably with every door and window open. I don’t recollect ever to have suffered as much from heat as we have done this summer.” Fierce weather could wilt fall crops, scorch voter turnout in winter, or sink spring ships bearing news and mail. Jefferson saw that better record-keeping was key. He harvested data and spun through scenarios, weighing agricultural needs against new innovations.

Where and when could American farmers grow the best strawberries, olives and grapes? Which bird calls signaled a change of season? Armed with a pencil and his reusable ivory notebook—wiped clean weekly as he transferred data, spreadsheet-style, to his papers—Jefferson struggled to make useful links between climate and geography. “For example, no one had yet worked out empirically what the differences might be in the weather of Philadelphia and Virginia, or between lower and higher elevations of land,” McClure says. “His motivation seems to have been to fill out parts of that big picture.” Jefferson clocked winds, listed temperatures, ranked rainfalls. He made sure his at-home weather lab was well stocked and ready for chance discovery.

“What impresses me about Jefferson and other colonial scientists is how attuned they were to the natural world around them, and, specifically with Jefferson, how he was at a forefront in quantifying these weather observations over time and across geography,” says Daniel L. Druckenbrod, an environmental scientist at Rider University. Jefferson not only invested in thermometers, hygrometers and barometers, but he also kept up with theoretical trends and shuffled around his tech to refine readings. He sought out clues to decipher how and why, exactly, the natural world worked the way it did. Constant travel spurred his progress. “His interest in seemingly everything around him is really fascinating—noting when the rye harvest began in Paris in 1787, a cherry tree losing leaves at Monticello in 1778—I imagine that not much escaped his attention,” says Jennifer Stertzer, director of the Center for Digital Editing. She finds Jefferson’s handwritten format akin to an analog database.

The Native peoples of the American South also tracked changes in waterways and landscapes, guided by the belief that “there existed no line between the human and natural worlds,” says Gregory D. Smithers, a historian at Virginia Commonwealth University. “Indigenous people didn’t view the environment as a thing; it wasn’t chattel that you could fence off, divide into neat little grids on a map, and buy or sell. Indigenous people sought to balance their need for sustenance with the local environment’s ability to provide that sustenance. It was a balancing act, a spiritual and physical quest for harmony.” Jefferson’s take was one of many worldviews in an America growing vaster by the day.

Jefferson’s daily weather observations for July 1-14, 1776/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c5/7d/c57dfbd3-cff2-4108-a986-4772a387a697/3864_tjmemorandum_p128_work_optimized_0.jpg)

Early America buzzed with weather watchers. Scholarly elites traded reports in international societies like the one Jefferson led, the American Philosophical Society (APS). Madison, the nation’s fourth president, was one of many who echoed Jefferson’s scientific style. His journals capture conditions at his Montpelier estate between 1784 and 1793, now available via the Historic Meteorological Records project at the APS.

Madison’s handiwork—sometimes aided by assistants—offers new vistas on plantation life. Take, for example, his record of a 1791 drought. The extreme heat “threatened Madison’s corn, as well as the private and communal gardens of the people he enslaved,” says Bayard Miller, associate director of digital initiatives and technology at the APS. Madison’s data harvest swept up the dates and times when peaches or strawberries were “first at table” or a “barbacue” drew guests. A walk through Madison’s weather notes widens the archival view to reframe the enslaved people who did that labor.

What these founders knew about the weather ruled their daily paths as farmers, politicians and enslavers. “While Jefferson probably was recording the ebbing of the Little Ice Age, Monticello’s microclimate might have been changing even more as Jefferson ordered woodlands and forests cleared for wheat,” says Emily Pawley, a historian at Dickinson College. “More and more of Monticello would have been exposed to harsh sunlight and wind.”

A 1788 portrait of Jefferson by John Trumbull/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/94/47/94478dfa-12c9-467b-8027-ac0bb6df97f6/thomas_jefferson_by_john_trumbull.jpg)

With his local world in flux, Jefferson welcomed a new generation of colleagues. By the 1820s, Americans enjoyed another scientific revolution. Cheaper, steadier thermometers meant wider use. Jefferson happily watched networks of weather observers spring up across state lines, forming a prequel to Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry’s mid-19th-century crowdsourcing campaign to create the National Weather Service.

Weather, Jefferson thought, had a history worth keeping. His insights now help us imagine past climates with greater precision and reveal how people dealt with extreme events. Weather records supply more than background scenery for the historian’s quill. “As global warming takes us into a different world, climatically speaking, it will take some careful reconstruction and imagination to grasp the differences between Jefferson’s time and ours,” says Sam White, a historian at Ohio State University. “Just as we preserve the archives, architecture and artifacts of that era, we will have to preserve records of its weather and climate to understand what it was like to be there.”

#Discover #Thomas #Jefferson #Meticulously #Monitored #Weather

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/ff/03ff088c-e3b2-4442-bb10-d48969be918b/tj-weather2.jpg?w=585&resize=585,99999&ssl=1)